When we make financial investments we tend to act completely selfishly. Even with ethical investments our aim is to make a return on the amount we put in. This article seeks to quantify lockdown as an ‘investment’ of pure self interest, variously for different age groups. Everyone has made sacrifices of their freedom and months of their lives to decrease the risk of death for everyone. But will our ‘return on investment‘ (ROI) be worth the price?

One of the key ways that regular economic investments are evaluated is the ‘expected value’. This is simply the average of what you might lose, or what you might win, multiplied by the probability of that outcome. In the case of a lottery ticket, let’s say it costs £2 and gives you a 1-in-a-million chance to win £1 million. The expected value of the lottery ticket is actually only £1 [ 1,000,000 * (1 ÷ 1,000,000) ]. Considering that this lottery ticket costs £2, it is a bad investment. To think of it another way, if you bought all of the 1 million lottery tickets available you would be guaranteed to win the 1 million pound prize, but you would have spent 2 million to get there.

So, why do people buy lottery tickets? This brings us to another key economic concept, the ‘expected utility’. This concept tries to capture the subjective feeling of loss or gain for a given outcome. For instance, perhaps the loss of £2 really doesn’t worry us at all, but the idea of gaining £1 million pounds is monumentally exciting. Therefore we are happy to pay for the ticket. Because a huge dose of happiness divided by 1 million, outweighs the tiny (but almost certain) negative feeling caused by a loss of £2.

The cost of not locking down

To evaluate lockdown I will ignore the financial cost for now and deal with time as the crucial variable. The key quantity will be years of life, or of years of quality life. In a nutshell, someone young has more years to lose if they were to die but they also are much less likely to die. Someone very old has fewer years to lose but is very likely to die if they caught COVID. On the other hand, they might only have a few years left anyway. The loneliness of lockdown away from their family might not be how they’d choose to spend their last moments if they had the choice of a higher risk of death but more quality time.

What is the quality of life cost of lockdown for you?

In order to calculate the cost of lockdown you would have to quantify how much you suffered by living under lockdown. This is probably unique for each person’s experience of lockdown. This is equivalent calculating your decrease in ‘expected utility‘.

For a thirty day month of lockdown, how many of those days would you exchange for days where life was back to normal? Would you happily trade half the days? By which I mean you could swap one month of lockdown for normal life, but in return you must give up fifteen days later on. For arguments’ sake, opting to die fifteen days sooner. For some people they might just trade a few days. Lockdown might only impact them in small ways, so they might propose to trade three days per month (10%). On the extreme, some might find the loneliness, lack of freedom, lack of travel, separation from loved ones, financial losses, intolerable and might trade all thirty days. This is equivalent to saying they would happily die a year earlier to erase 2020 altogether.

Conversely, some people might secretly enjoy lockdown, because they are introverts, homebodies, struggle with FOMO, have had an extended paid holiday due to furlough, or would normally endure long tiresome commutes to work. These people on balance have ‘won’ in lockdown and might say they’d actually trade some days of life as normal to have more lockdown days. For myself (in the 35-44 year old category) I’m going to wave my finger in the air and say that I would trade ten days per month. I’ve found the isolation of lockdown pretty horrible.

Average days of life lost per person

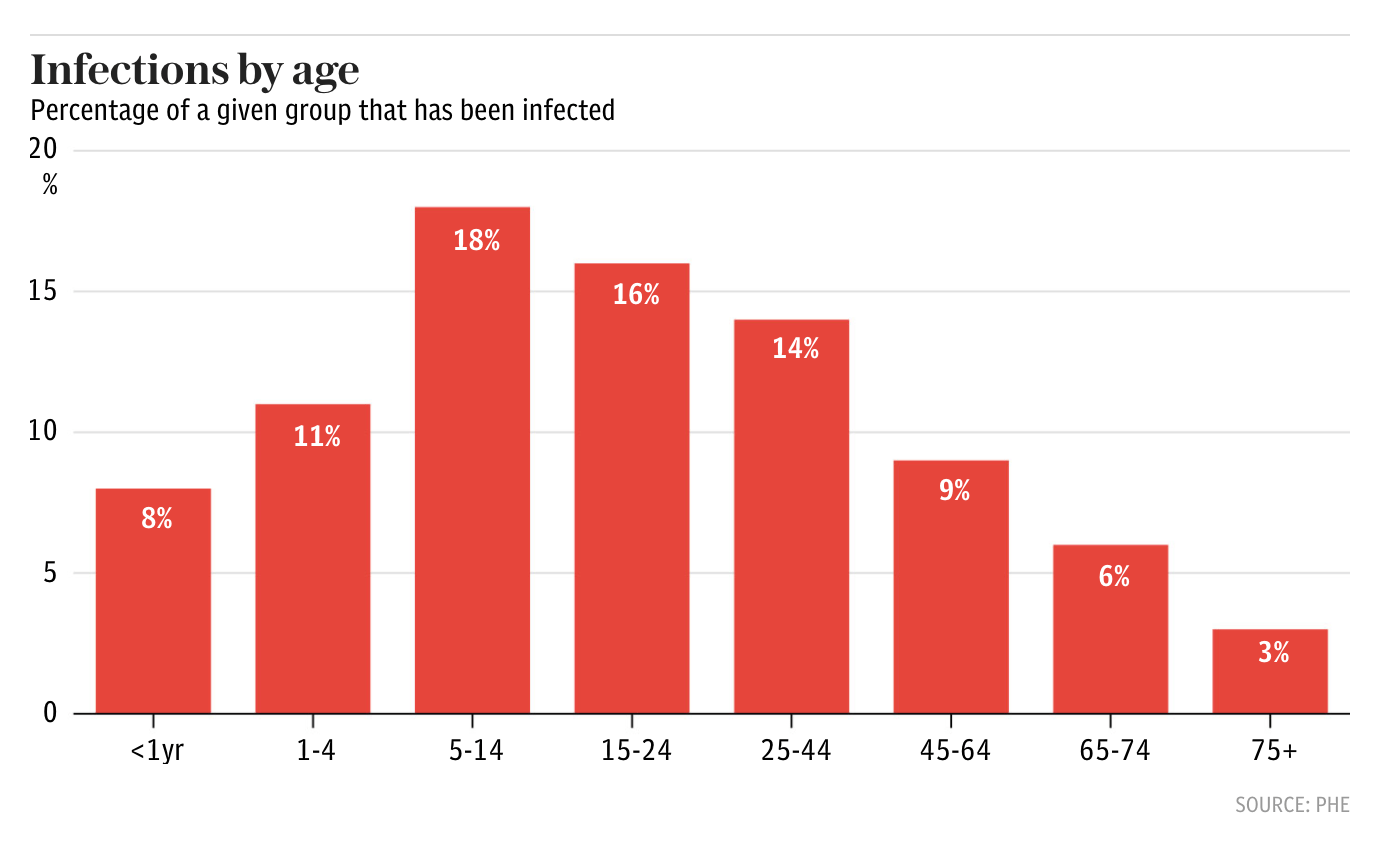

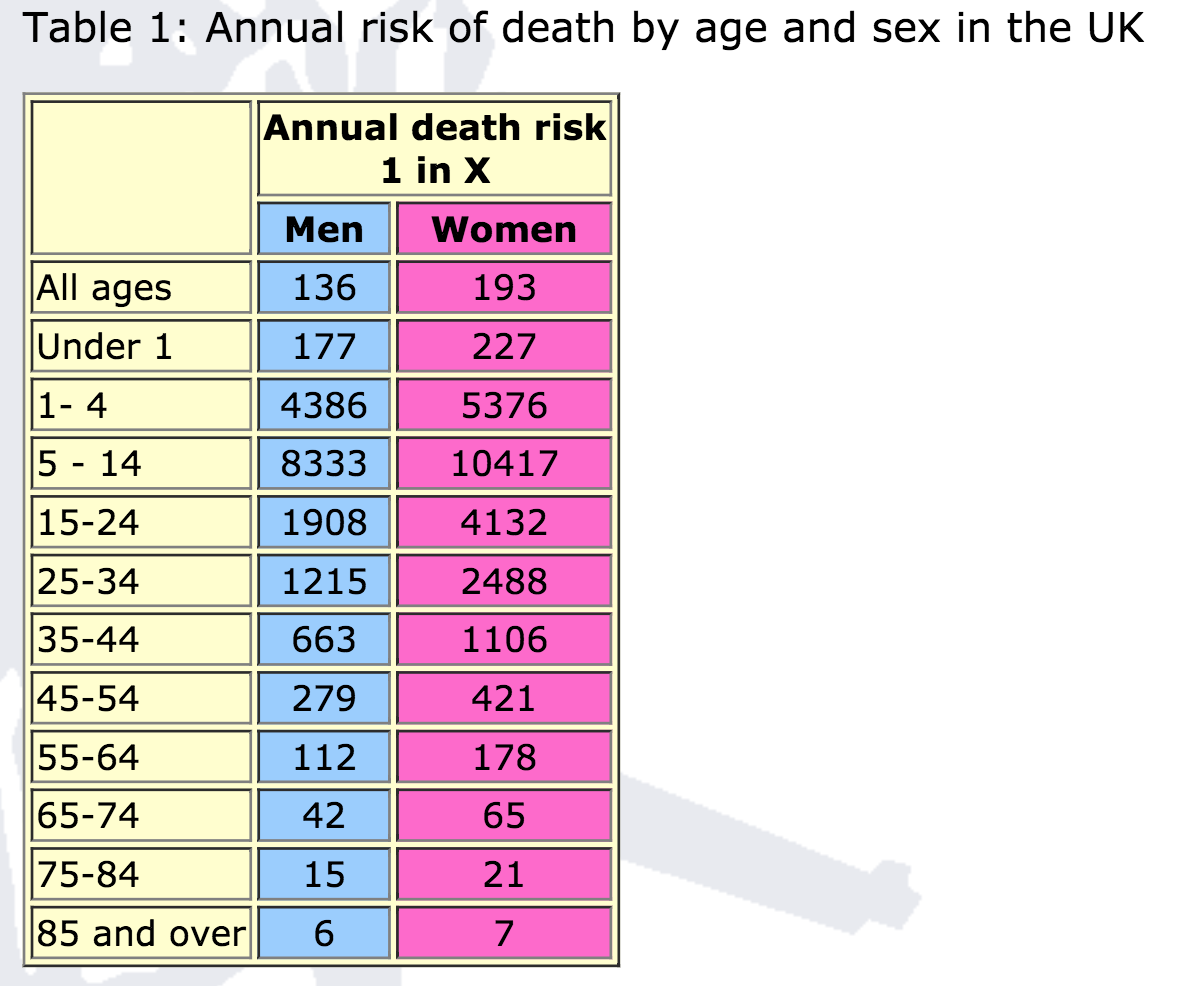

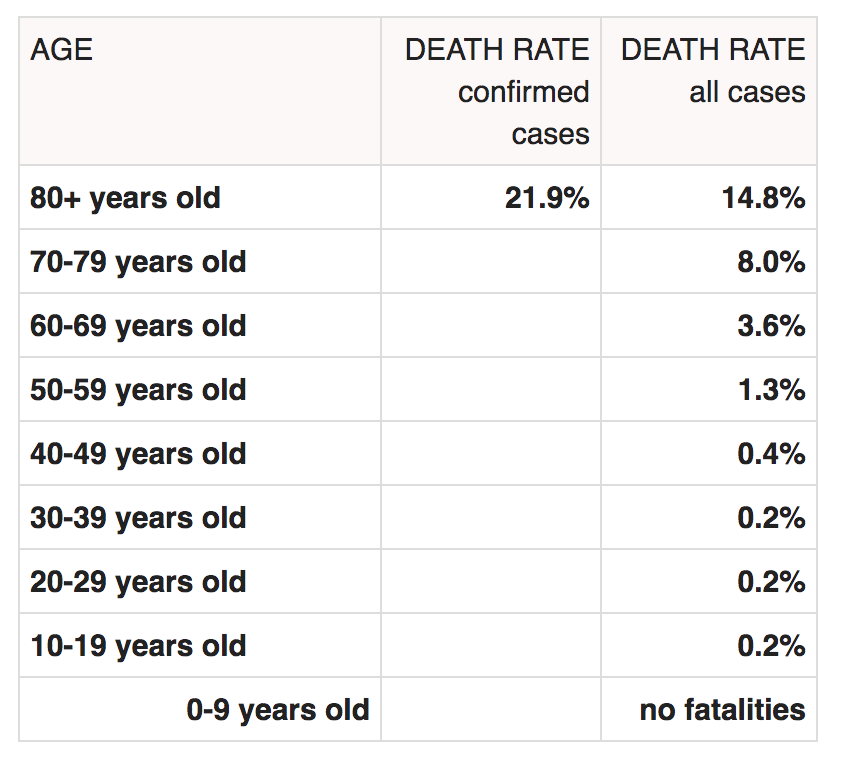

In order to have something to compare, I have calculated the ‘expected value’ for time lost due to COVID under actual versus worst case scenarios (e.g., no restrictions) for each age group. Just as this was calculated for the lottery ticket example above, this is the probability of dying within 28 days of a positive COVID test multiplied by the number of expected years each age group had left to lose.

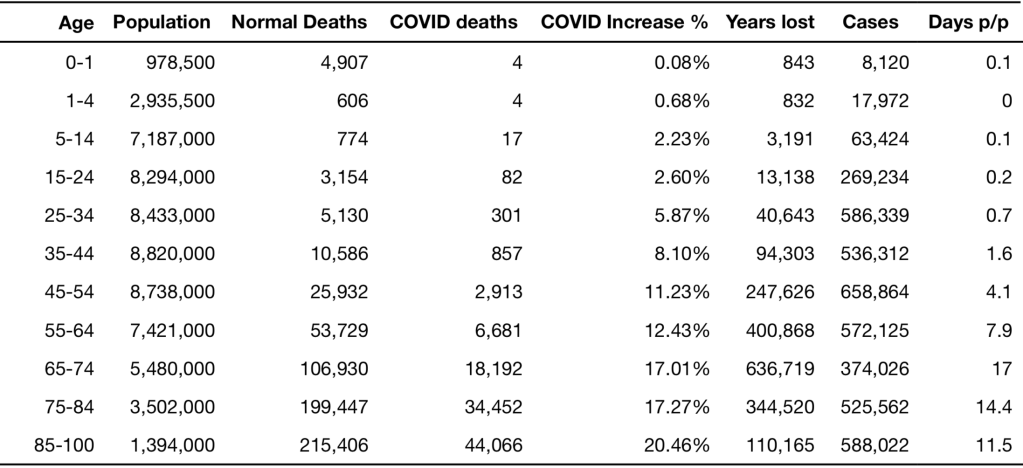

This is presented for eleven UK population age groups in Table 1. I initially chose to quantify these lockdown benefits using ‘years of life’ saved. A twenty year old who died of COVID might have lost 65 years of their life, but at the same time, the number of deaths in twenty year olds is 1 in 100,000. After starting the calculation I realised that the final numbers became tiny fractions and so it’s actually easier to organise these results using average days of life lost per person.

For those up to 35 years old, the number of days lost per person due to COVID deaths is comfortably less than one day (see the final column of Table 1). You could say even if lockdown had reduced the quality of their life by a single day in the whole year of 2020, more days of quality life had been lost due to lockdown than due to coronavirus.

This average value for days of risk does increase with age: by 50, the expected loss is four days, then it becomes seventeen days at age 70. Counter intuitively, it is only eleven days above age 85 even though they have the highest mortality rate. This is because this group had fewer days remaining to live due to their increased age. So the greatest average loss of life is for the 65-75 years age group.

Days of life saved under best and worst case scenarios of not locking-down

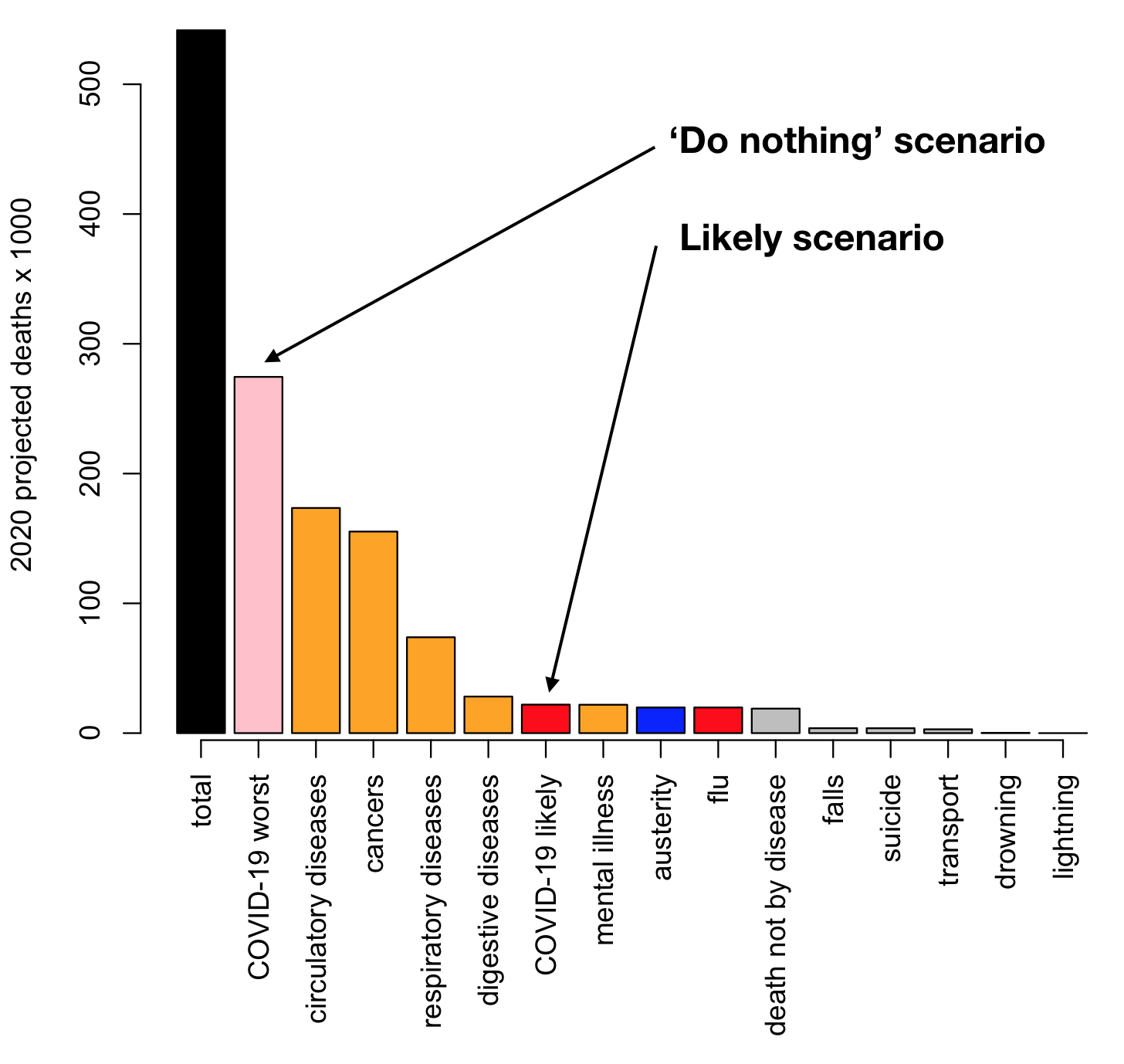

These numbers so far (Table 1) are just actual loss of life whereas the dividend for lockdown is to save lives. The estimate I am using for number of lives lost in a hypothetical scenario of no lockdown or distancing is 250,000 deaths for the ‘best’ case, moving up to 500,000 for the ‘worst’ case.

It’s easy to convert to lives saved because we had roughly 100k deaths in the year since the pandemic began. We can just multiply by 2.5 and 5 respectively, subtracting the actual losses, to get number of days of life saved by lockdown.

For 35 year olds in the best-case scenario lockdown has saved one day per person, or up to three days in the worst-case scenario. For 50 years olds we saved between six to sixteen days respectively; for 70 year olds between 25 to 68 days; and for 85+, between seventeen to 46 days of life were saved. For a ten year old the worst case scenario implies about one third of one day (eight hours) was saved. Note that these results are not days per year, or days per month, they are average days saved across a person’s whole lifetime.

Accounting for acute illness and long COVID

If we want to be fair about the negative consequences, we should probably include time being sick with COVID symptoms, and the effects of ‘long COVID‘. Similarly to the death risk I’ve multiplied the probability of these outcomes by the duration of symptoms within each age group. These results summarised by average days lost per person are presented in Table 2. There is a natural split at about 45 years of age where below this age, the risk under the worst-case scenario is small, at 11.2 days or less, while above this threshold the expected risk is substantial, between three to twelve weeks.

A worked example

Finally, we arrive at the summation of the total life-cost and the life-savings attributable to lockdown. My self-assessed cost of lockdown was ten days per month. This comes to 100 days in total for the last year if I admit to being able to live a little more normally during the two months of summer. In my age bracket’s worst-case scenario, the number of days of my life I’ve saved not dying of COVID, not having COVID, and not getting long-COVID is 11.2. So, by these calculations I’ve made a net loss of 89.8 quality days over the last twelve months by locking down. This was a poor ‘return on investment’ for me from a purely selfish point of view. I’ve only gotten back one tenth of the time I lost.

A raw deal for young people

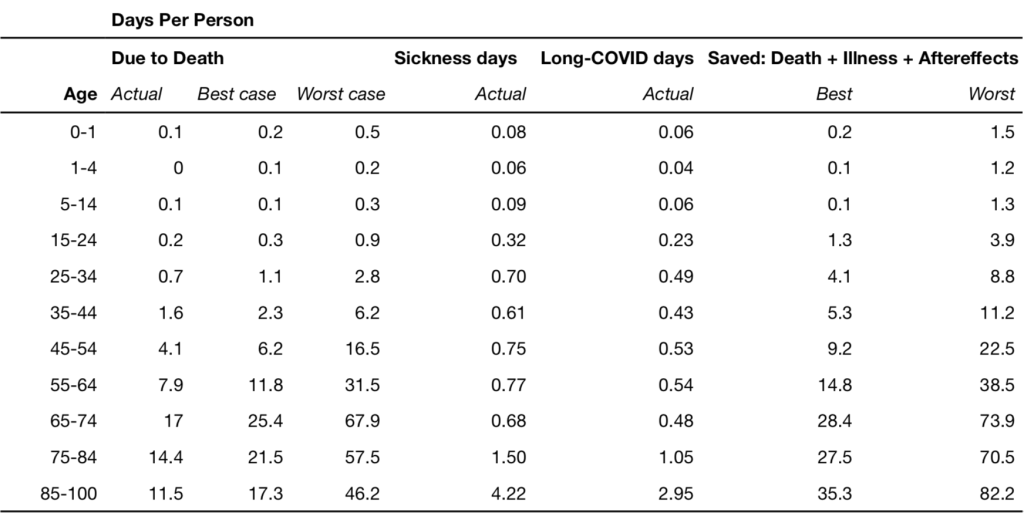

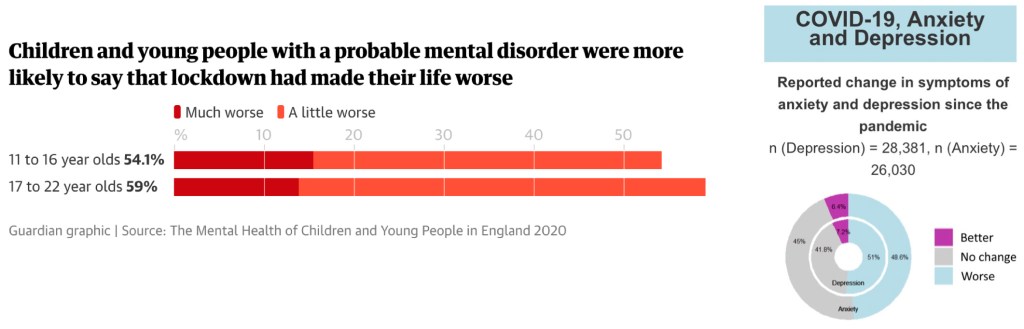

Returning to the question of how many days per month you would give up to avoid lockdown, for comparison we need to divide the lifetime number of risk days by the 12 months under lockdown/restrictions. The statistical equilibrium to balance these lost days comes to one day (or less) per month for under 45’s, or between two and seven days for over 45’s. So, if your number of lost quality days per month was below whichever of these thresholds applies to you, then you’ve made a good return on investment for lockdown. Conversely, if your number of days was above these thresholds, the sacrifice you have made over the last year was greater than the amount of standardised risk you avoided. If I were to imagine that I had survey results from these same age groups, I would be willing to bet that most people under 40 were net losers, and that for over 40’s lockdown has come out as much more of a personal benefit. This is a simplification, and furthermore, the dichotomy is not really surprising as age related risk has certainly always been part of the public discussion. But the numbers are pretty stark for young people. Only about 2% of youths who died this year died due to COVID. Meanwhile young people suffered significant disruption to their education, the early part of their careers, and mental health.

Older people aren’t the only vulnerable ones

Lockdown has been hard on the 9 million people in the UK suffering from loneliness. Loneliness is a serious killer that has a global health detriment equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day. Roughly 50% of people have had an increase in depressive or anxious symptoms (Figure 1). More than 2 million operations have been cancelled, which could lead to substantial numbers of lives lost due to neglect of other medical issues. Estimates are that 3 million cancer diagnoses might be delayed, and that a lockdown of six months would lead to an extra 173,540 years of life lost due to cancers that should have been caught earlier. More will suffer from mental health issues and those already suffering are reporting a greater reduction in their quality of life during lockdown. Predictions are that suicide will increase by 10%. There was a 50% increase in domestic violence helpline calls during the first lockdown in April.

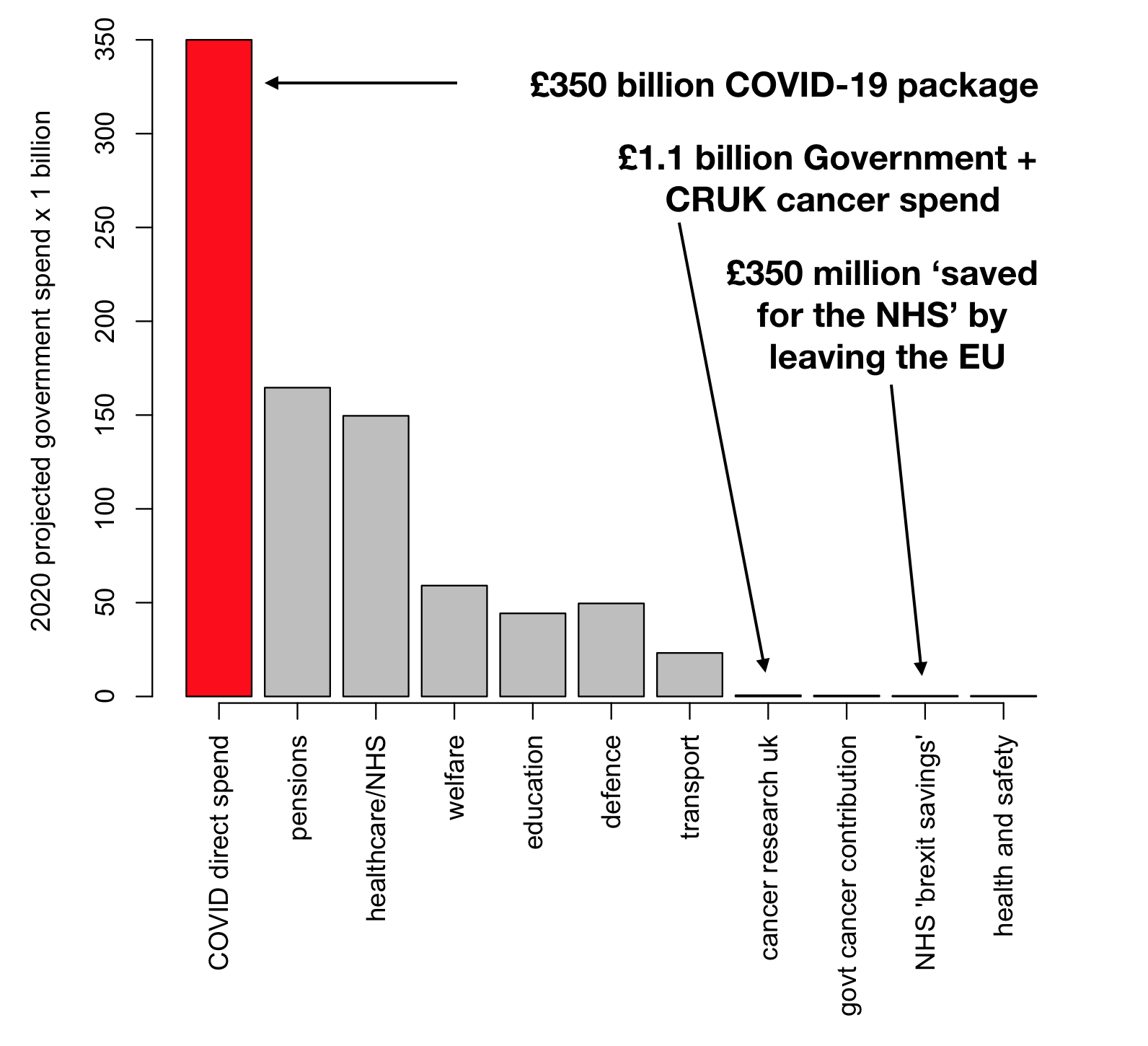

The cost of COVID for the government so far has been roughly £330 billion which is about £11,000 per working adult in the UK. The austerity applied by the UK government as a result of the 2008 financial crisis is estimated to have killed 131,000 people, which is more than COVID has killed to date. Unemployment is also a killer, with US figures suggesting that for every 1% increase in unemployment 37,000 people die (equivalent to 6,700 in the UK population). The unemployment rate during the crisis increased by about 1.5% but has recovered a little since vaccination began in 2021, but is still more than 1% worse than 2019.

Don’t thank the young with vaccine passports

There is a lot rhetoric around in COVID times thanking essential workers and NHS staff. This is totally fair because these people are working hard and risking their own health to save lives and keep society functioning. But, I believe we should also be strongly aware of the sacrifices made by young people who undergo significant sanctions to their freedom, well being and long term financial prospects, despite having little personal risk due to COVID. Young adults were about 1000 times more likely to have lost their job than to have died of COVID in 2020. In the context of vaccine passports I think it will be crucial to delay any such measures until people of all ages have had a chance to be vaccinated. Otherwise this will be yet another kick in the teeth to the younger group who had the least to gain from all of the restrictions.

Of course, most young people will also have friends, family, colleagues and live in communities involving people of varying ages. So, it’s not all about self interest, but this individualistic comparison is rhetorical within this article.

It’s not all doom and gloom

There have been some positives to come out of this crisis, and not just for Amazon and Netflix. More people are exercising and riding bicycles. There have been reductions in some types of air pollutants lasting for months on end. Some people will have had time to take stock of their lives, up-skill, make self improvements, save money. People will almost certainly learn to be more grateful for the little things, and to cherish their friends and family. Events like this can also be a wake-up call and hasten society to seek positive changes. For such extraordinary events sometimes negative events can have an overall positive effect over the long term due to the systemic changes they bring about.

None of this calculus and comparison really matters

Analogous to the importance of proper risk-management in the financial world, expected return isn’t the only factor in choosing investments. Avoiding catastrophic outcomes should always be factored into your strategy.

I think if you really did the sums on an individual level lockdown has likely taken away more than it saved in terms of years lost and illness. But, this doesn’t mean that it was the wrong decision. Even if you wished to take the approach of ‘survival of the fittest’, it would not be pragmatically possible.

Unless this approach was taken unilaterally worldwide, your country would inevitably suffer impacts from restrictions on trade and travel made by other countries, and likely be subject to sanctions due to their rampant infection rate. Secondly, at its theoretical limit, such an abandonment of vulnerable individuals would never be morally tolerated by society.

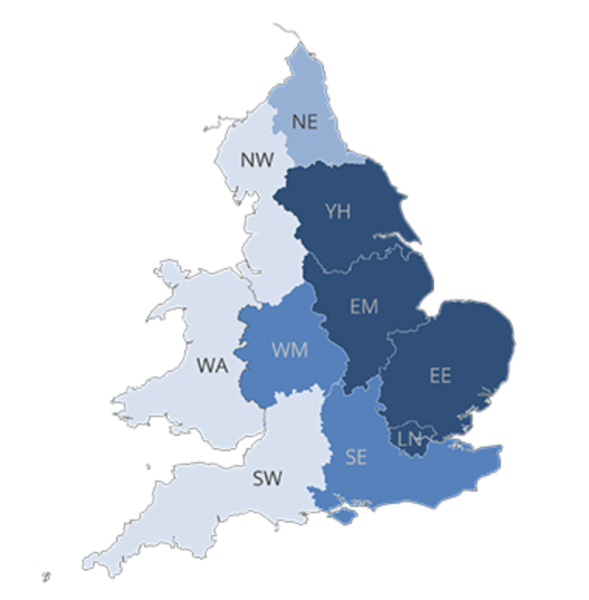

Most crucially, at the peak of the crisis we saw over 1,000 UK deaths per day and hospitals were at breaking point. Double, triple or quadruple this, and you would have a humanitarian disaster. Mass collections of bodies, the army patrolling the streets. A possible outcome of persisting with this approach would be a serious break down in essential services and public order, which could lead to loss of confidence in the government, loss of confidence in the economy, looting and even food shortages (Figure 3). Problems such as we have seen with lack of access to healthcare due to lockdown would be even worse under this scenario. Levels of day to day fear of the virus would be extreme if prevalence had reached four times the worst we have experienced so far.

It was simply never feasible to avoid restrictions which explains why no country took this free-for-all approach (at least not for the duration of the crisis). Countries in Asia and Australasia, who due to geopolitical luck and swift action, were able to lock down very early on and very effectively, were able to provide a much safer environment for their populations, and a much freer daily life, with relatively few restrictions versus Europe and America.

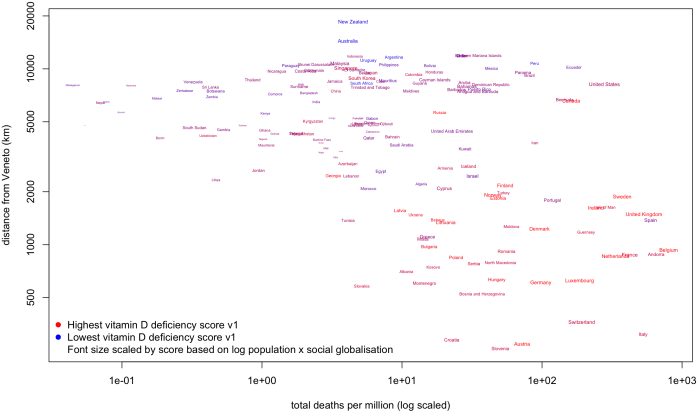

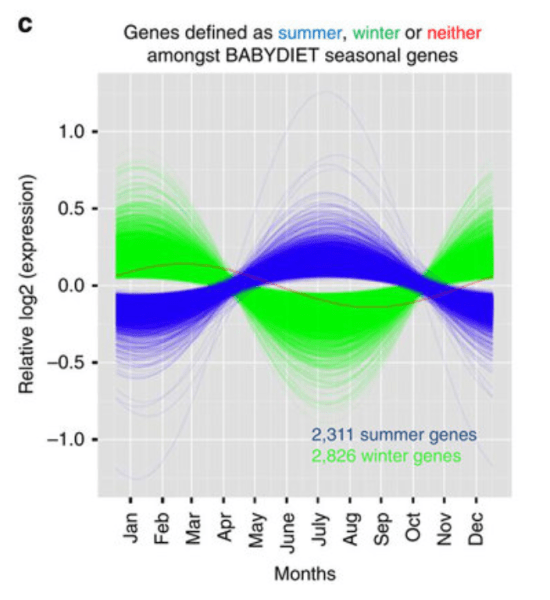

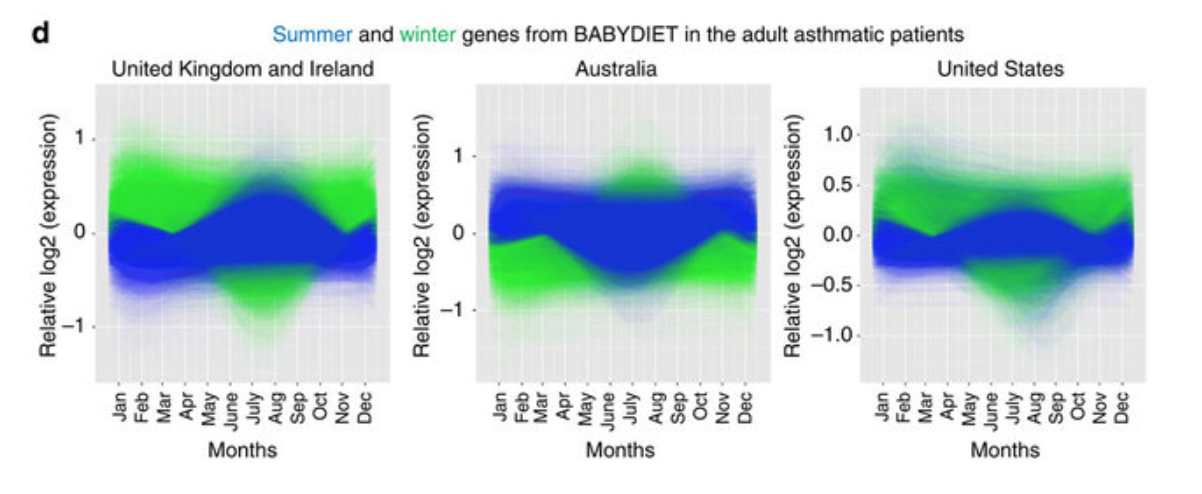

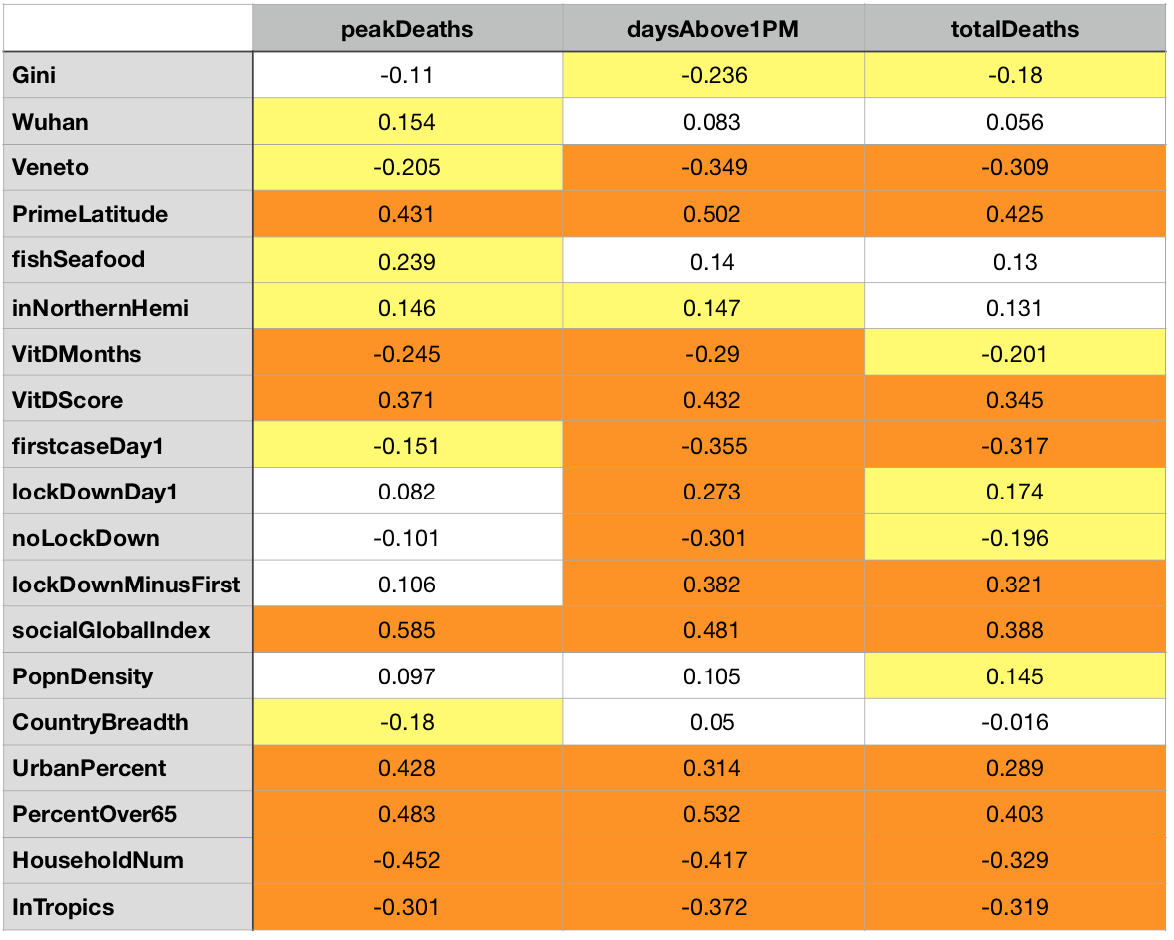

The vaccines are very effective (importantly there was always a chance that they would not be) which has strongly vindicated this approach. You can retrospectively point fingers at herd immunity strategies proposed early on by Boris Johnson and Donald Trump. But, it may not have been possible for Europe and the USA to maintain strict enough control for an Australian-style approach to succeed. Those countries are much more highly connected to the rest of the world, more densely populated and were closer geographically to the epicentre(s) of the pandemic. Furthermore, the northern hemisphere was hit at a key time for infections to peak coincident with the typical flu-risk season (the colder months). Countries like Australia had more time to act, and as the crisis bloomed, were at the tail end of summer where people are less likely to become ill or pass on airborne viruses.

So what is your ROI on lockdown? I would propose it is the upholding of society as we know it! Regardless of your age we’ve lost a lot, but we’ve all come out ahead. The price of not locking down was always impossible.